- Home

- ILIL ARBEL

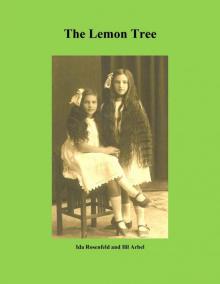

The Lemon Tree

The Lemon Tree Read online

The Lemon Tree

Ida Rosenfeld and Ilil Arbel

Copyright © Ilil Arbel, 2005

All rights reserved and remain with Ilil Arbel. Except for review, no part of the publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information retrieval system without permission from the author.

Also by Ilil Arbel

Madame Koska and the Imperial Brooch

The Cinnabar Box

The Ecology of Nature Spirits

Miss Glamora Tudor! (The New Chronicles of Barset, Book One)

Their Exits and their Entrances (The New Chronicles of Barset, Book Two)

Annunaki Ultimatum: End of Time

On the Road to Ultimate Knowledge

Strange and Curious Plants

Maimonides

Witchcraft

Medicinal Plants

Favorite Wildflowers

Favorite Roses

Ida Rosenfeld, née Wissotzky

To the Wissotzky family and their magnificent dreams,

so many of which were actualized.

List of Illustrations:

Front Piece: Ida Rosenfeld, née Wissotzky

Chapter One: Siberia

1: Hadassa (left) as a university student, with friends

2: Hadassa as a young woman

3: An invitation for the wedding of Hadassa Winitzkaya and Avraham Wissotzky

4: Biysk, the town where the Wissotzky family lived in Siberia

5: Hadassa, Avraham, and Sasha (sitting on the fence) with young relatives

6: Ida as a baby

7: Sasha, Ida, and Feera

8: The children with friends

Chapter Three: Mourning

1: After the illness. Ida’s hair had to be cut because of her extremely high fever

2: Grandpa Leib (center) with his family

3: Aunt Rose on a ship, during one of her many trips to Israel

4: The girls with an uncle and his baby

5: The girls with an uncle and a family friend

Chapter Seven: City of Lanterns

1: Official papers from the Chinese Consulate in Irkutsk

2: The Hongkew market in Shanghai

Chapter Nine: Another Variety of Ship

1: On the ship to Port Said

2: With a group of refugees in Port Said

3: A Camel Caravan in Port Said

Chapter Ten: Home

1: A typical apartment house in Tel-Aviv

2: Avraham’s dental office in Tel-Aviv

3: In the park at Yehuda-ha-Levi street; Hadassa in the background

4: An early lending library card

5: Ida with a friend, dressing up

6: Sailing on the Yarkon River

7: Ida and Ada as teenagers

Epilogue

1: Dr. Avraham Wissotzky

2: A portrait of Feera

3: Feera as a young woman

4: Ida on a ship heading for France

5: Ida in Nancy

6: Leibek in Nancy

7: Ida’s bust, created by an Israeli artist

8: Another bust modeled after Ida

9: Ida, painted by an Israeli artist

10: Allenby Street, 1933

11: Leibek’s office in Tel-Aviv

12: Feera and Moshe Mishory

13: At the seaside café in Tel-Aviv

14: Ida and Leibek with their children

15: Yaffa, Ida’s childhood friend, poses as a stylish young woman of the 1930s

16: Ora, Ida’s childhood friend, with Ida’s son (right) and her own son

17: The Habima Theatre in Tel-Aviv

18: Ida’s and Feera’s older children

19: Ida’s and Feera’s younger children

20: The sisters

INTRODUCTION

A unique, valuable tale is the birthright of every human being. Often it is overlooked, since we are accustomed to the biographies of great people, and read the history of nations. But the personal stories of ordinary people may be, in the end, a better record of life as it was lived in a specific period of time. The preservation of oral histories is important to families, of course, but I believe it goes further and may interest a much larger audience. Some years ago I wrote a biography of a very great man, the philosopher Maimonides. During my research I came to the conclusion that what made this man so interesting to read about was not his relationship with the high and mighty Saladin, or even his magnificent books that have continued to influence Western culture for over eight hundred years. What really touched me were the details that showed his humanity; his undying love for his lost younger brother, a letter to a friend that described Maimonides’ exhausting schedule and debilitating fatigue, and his staunch legal defense of a young woman deserted by her callous and unfeeling husband. Such matters do not belong to the celebrated. They might have happened to anyone. In addition, I simply could not tear myself away from the letters of ordinary people found in the Cairo Geniza (an extensive collection of documents discovered in a synagogue in Cairo) that revealed so much about daily life in Maimonides’ times.

I hope this book supports such a claim. The Lemon Tree is the true story of the pioneering Wissotzky (pronounced Vissotzky) family, and the extraordinary year they spent on the road on their way from Siberia to Tel-Aviv. It is narrated by Ida (pronounced Eeda), the younger daughter. The book is based on her written memoirs, with a lot of additional material taken from her stories, told to me orally over decades. She was a marvelous storyteller. I struggled to keep her distinctive voice, entirely submitting my writing style to hers – and I am convinced that I accomplished my aim.

The Lemon Tree is the first of three books. Eventually, I hope to publish them together as The Aliya Trilogy. The other two – Tel-Aviv and Green Flame, are novels written by the father, Dr. Avraham Wissotzky. They are fiction, but both describe true pioneering experiences. These three books belong together.

As is my custom, prior to submitting the book to the publisher, I ran it by four readers and a professional editor. I chose my victims carefully for this book. Two of my readers have family connections to the Wissotzky family, and knew them well. In addition, they are extremely knowledgeable university professors, and one of them is a historian who lives and works in Tel-Aviv. The third reader is a director of recreation in an establishment that cares for senior citizens. She is constantly involved with oral histories and memoirs, and has developed a serious degree of expertise in this genre. The fourth reader is an artist; she has deep knowledge and interest in history, and is familiar with the period. I asked for feedback and comments, which they generously gave.

As for the editor, I gave him a horrible task. “Fix my mistakes,” I commanded, “but do not dare change the narrator’s voice!” I can only justify my imperious behavior by the fact that I had to do exactly the same, and between us, Ida’s voice is retained, loud and clear.

Many thanks to my editor, Mr. Gregory B. Ealick, and to my readers, Professor Avigdor M. Ronn, Professor Alexander Mishory, Ms. Dianne Ettl, and Ms. Patricia J. Wynne. Their help was invaluable.

– Ilil Arbel

CHAPTER ONE: SIBERIA

We crushed together into the warm entrance hall, pushing each other, laughing and stomping the snow from our boots. Outside, our coachman led the horses into the stables. “Hurry up with your coat, Ida,” said Marusia, our nanny. “Your nose is frozen again. We must take care of it immediately.”

“My nose always freezes worse than Sasha's and Feera's noses,” I wailed. “It's unfair!”

“Redheads with delicate skin freeze worse than other people,” explained Marusia patiently for the thousandt

h time. Papa poked his head out of his dental office, smiling. “Come, I'll rub your nose with snow and put some goose fat on it,” he said, coming to hug us. His patient, an old peasant I knew well, followed him. The peasant smiled at me and said kindly, “Never mind your nose, little Ida. Some day you will be the loveliest girl in all Siberia. Here, I have a little present for you, to make you look just like a real princess.” He handed me a small lump of raw gold. “I am not so little,” I said proudly. “I am almost seven years old. Thank you, Ivan Petrovich. What a beautiful necklace this will make – I will wear it when I grow up and go to balls and parties!” Ivan Petrovich laughed and patted my head.

Gold was present in Siberia in large quantities. Peasants found it in their lands and fields and often, instead of paying with money, they removed a small bag that hung around their necks, took out raw lumps of gold, put them on the table and said: “Doctor, take as much as is due to you.” Among the patients visiting Papa's office many peasants paid that way and Papa kept a small collection. But this piece was special. It had a hole naturally formed through it, and seemed shinier than the usual lumps that looked much like golden earth, crinkled and full of little holes. Marusia fished a piece of string from the bottomless pocket of her embroidered apron, strung the gold and hung it around my neck. “And one for Feera, and one for Sasha,” said Ivan Petrovich, generously handing out the pieces. He sighed heavily. “Teeth, teeth,” he said to Mama who had just stepped in from the dining room, always sympathetic to people's woes. “Believe me, in the days of my father no one had problems with teeth . . .” He wrapped himself with his heavy fur hat and coat, and lumbered like a polar bear on his long walk home. I always marveled how the peasants managed to walk so comfortably, even on ice, with their feet wrapped in nothing but layers upon layers of rags. The cold never seemed to bother them, though I remember days when the temperature reached fifty degrees below zero!

Papa and I followed him outside to take care of my frozen nose. Papa rubbed it with snow, really hard, then smeared it with fat. The nose started thawing, turned red, and hurt as if pricked with needles. But I didn't care. I felt like a princess with the gold hung around my neck.

***

My memories from Siberia are of one big party. Taking trips to the woods to collect bluebells in spring and wild berries in summer. In winter, skating on the ice, throwing snowballs, and building huge snowmen with coal eyes. Traveling in troikas, large sleds hitched to three horses. Pushing our little child-size sleds, running madly, then jumping to lie on them and glide for unbelievable distances on the uninterrupted sheets of ice, feeling as if we were flying.

During winter, life naturally concentrated mainly inside the house. The windows in our house were doubled, with two sheets of glass to protect us from the heavy winds. All the cracks in the window frames were covered with thick felt, to retain the warmth inside the house.

Under the dining room window stood a tropical jungle. Mama could raise any plant, anywhere, even in the arctic weather of Siberia. Her strong interest in the life sciences made her study medicine and become a midwife one of the first generation of women to be admitted into the University in Odessa, where she met and married Papa. Her father was the estate manager of a wealthy landowner and she grew up surrounded by huge orchards, gardens, and private woods. Mama had a special piece of furniture built for the houseplants, shaped like wooden stairs, stained dark brown, and hand rubbed with oil to a high gloss. Diverse plants stood on the stairs, arranged according to height. The rich, dark green leaves moved slightly in the air currents created by the ever-present heat from the giant stove and the occasional drafts when the door was opened. The intricate greenery looked magical against the white world outside.

***

The next day I woke up early, remembering that this was Sasha's tenth birthday. I knew a big secretthe nature of the best present and was terribly excited. It was still dark and bitterly cold, despite the stove in every room, and I hurriedly put on my wooly blue dressing gown and furry slippers before running downstairs to the warm kitchen. It smelled of cinnamon and cloves, since Mama was already creating the birthday cake, her arms deep into flour and sugar. No one could make and decorate cakes like her. Later in Israel, during a desperate shortage of eggs, butter, and sugar, she made cakes from powdered eggs, coarse flour and imitation margarine, and they were still the best cakes I ever ate. I remember her melting raw brown sugar with a tiny birthday candle to create decorations on those cakes, and I still firmly believe that if necessary, she could conjure perfectly good food from virtually thin air. She covered Sasha's birthday cake with white frosting and nautical designs in red, blue, and gold; the cook and the maid busily prepared various other goodies.

“Butter!” I said happily. Milk, cheese, and butter were just delivered from the farm that regularly supplied us, still quite frozen from the trip outside, and the cook prepared to put them in the pantry when I grabbed a butter cake and ate it just as it was, raw, sweet, and creamy. I loved nothing better than those round, fresh cakes of butter, wrapped in cabbage leaves. Mama laughed at my strange taste, but allowed me to indulge it. “Did they bring Sasha's present yet?” I whispered conspiratorially, licking my fingers. “Not yet. Marusia will bring it in the afternoon, during the party.”

Feera and I put on our best dresses and tied ribbons in our braids. Feera's rich, wavy, dark chestnut hair had never been cut, and at age eight already reached her knees even when braided. She had delicate features, blue-green eyes and golden skin, and I alternately envied and admired her beauty. I despised my own curly red hair and thought I was ugly. To give Feeracredit, she tried, again and again, to tell me that everyone thought I was cute, but I didn't believe her after all, she was my sister, and therefore partial! Sasha put on a sailor suit and hat; I thought he looked quite elegant and mature.

Many children came, accompanied by their parents who were to have their own party in the formal living room. All the children went for a ride in a procession of beautifully decorated troikas, the coachmen singing with us, the nannies playing their balalaikas, and the bells ringing in the quiet woods. The noisy caravan returned in the early afternoon as darkness fell, the stars came out in the velvety black, clear sky, and the cold became unbearable. We ate a sumptuous dinner, and the gorgeous three-tiered cake was served with kiessel, a thick, sweet drink made from wild berries that grew in the nearby wood. You dropped a little milk into the kiessel, and the milk traced delicate, branch-like forms all through the dark crimson, thick liquid. Later in Israel, where wild berries did not grow, Mama invented a new kiessel. Incredibly, she reproduced the drink from the red variety of the desert cactus fruit!

Finally it was time for the presents. Mama and Papa came in, followed by a procession of smiling parents and carrying a small, covered basket. With great ceremony, they put it on the table in front of Sasha. He opened it and stood still. A tiny, round, black ball of fur with white markings looked back at him cautiously with its large black eyes. Sasha picked up the little dog wordlessly and tenderly hugged it. The dog snuggled up to him and put its tiny nose in his hand. This was love at first sight, a love that never died. “Is this a boy or a girl dog?” Sasha whispered. “It's a girl,” said Mama. “I'll call you Palma,” said Sasha to the dog. Palma was the Russian name for a palm tree. Sasha had great interest in warm countries, particularly in the tales Papa told about Israel, described as the Land of the Palm Tree.

***

Darkness descended in the early hours of the afternoon and we filled the long evenings with various games, toys, and occupations. Palma became the main interest as soon as she arrived. Sasha acted as the chief caretaker and assigned Feera and me as his helpers. Soon, Palma became the center of a scientific experiment! Sasha wanted to keep her small; he researched and found that she had to be given a daily dose of a minute quantity of ground copper mixed with water. He regularly administered the medicine and Feera and I worked as copper grinders. Hours upon hours we sat by the stove in

the dining room, singing about sailors and seafarers as we rubbed copper coins with sandpaper, special stones, and other diverse equipment to produce the powdered copper.

Palma really never grew and remained small, rounded, and black with white markings. Why didn't she grow? Certainly not because of the ground copper; she probably was simply a naturally small breed. Perhaps she had no sufficient time to grow.

Despite the many toys we possessed, most of the games we played were imaginary. Wearing improvised pith helmets, we explored the dining room jungle, Palma prowling about the undergrowth as our trusty black panther. At other times, we sailed majestic galleons to faraway lands. Arranging chairs in a long row to simulate the ship, we would travel the seas, singing sailors' songs and eating, for a reason I cannot remember, quantities of chicken drumsticks. Perhaps Sasha tried to imitate the dry meat sailors had to eat on ships. We waived the drumsticks in the air, sang, and ate for hours.

Best of all, Papa could tell wondrous stories. We didn't know then, of course, that he would eventually write books for children and adults and be published in three languages. Still, we knew a good tale when we heard it. Every evening, without fail, we demanded story time.

“So which story do you want today, children?”

ANCIENT ALIENS: MARRADIANS AND ANUNNAKI: VOLUME ONE: EXTRATERRESTRIAL HOLIDAYS

ANCIENT ALIENS: MARRADIANS AND ANUNNAKI: VOLUME ONE: EXTRATERRESTRIAL HOLIDAYS Ancient Aliens_Marradians and Anunnaki_Volume Two_Extraterrestrial Gods, Religions, and Mystical Practices

Ancient Aliens_Marradians and Anunnaki_Volume Two_Extraterrestrial Gods, Religions, and Mystical Practices Madame Koska & the Imperial Brooch

Madame Koska & the Imperial Brooch Ancient Aliens: Marradians and Anunnaki: Volume Two: Extraterrestrial Gods, Religions, and Mystical Practices

Ancient Aliens: Marradians and Anunnaki: Volume Two: Extraterrestrial Gods, Religions, and Mystical Practices Miss Glamora Tudor!: The New Chronicles of Barset: Book One

Miss Glamora Tudor!: The New Chronicles of Barset: Book One The Cinnabar Box (Guardians of the Earth)

The Cinnabar Box (Guardians of the Earth) Madame Koska and Le Spectre de la Rose

Madame Koska and Le Spectre de la Rose The Lemon Tree

The Lemon Tree Their Exits and their Entrances: The New Chronicles of Barset: Book Two

Their Exits and their Entrances: The New Chronicles of Barset: Book Two